Gods & Demons – Heritage Arts and Crafts of West Bengal

To keep the beautiful spirit of the London exhibition alive we have created a visual archive of the exhibits so that you can relive the beauty of the craft and visit them over and over again.

Like the arts and crafts of West Bengal, Gods and Demons is a topic that remains relevant and captivating in the twenty first century. The theme of good and evil is not only the starting point for the genesis of Patachitra and Mukhosh, but has enchanted audiences for thousands of years.

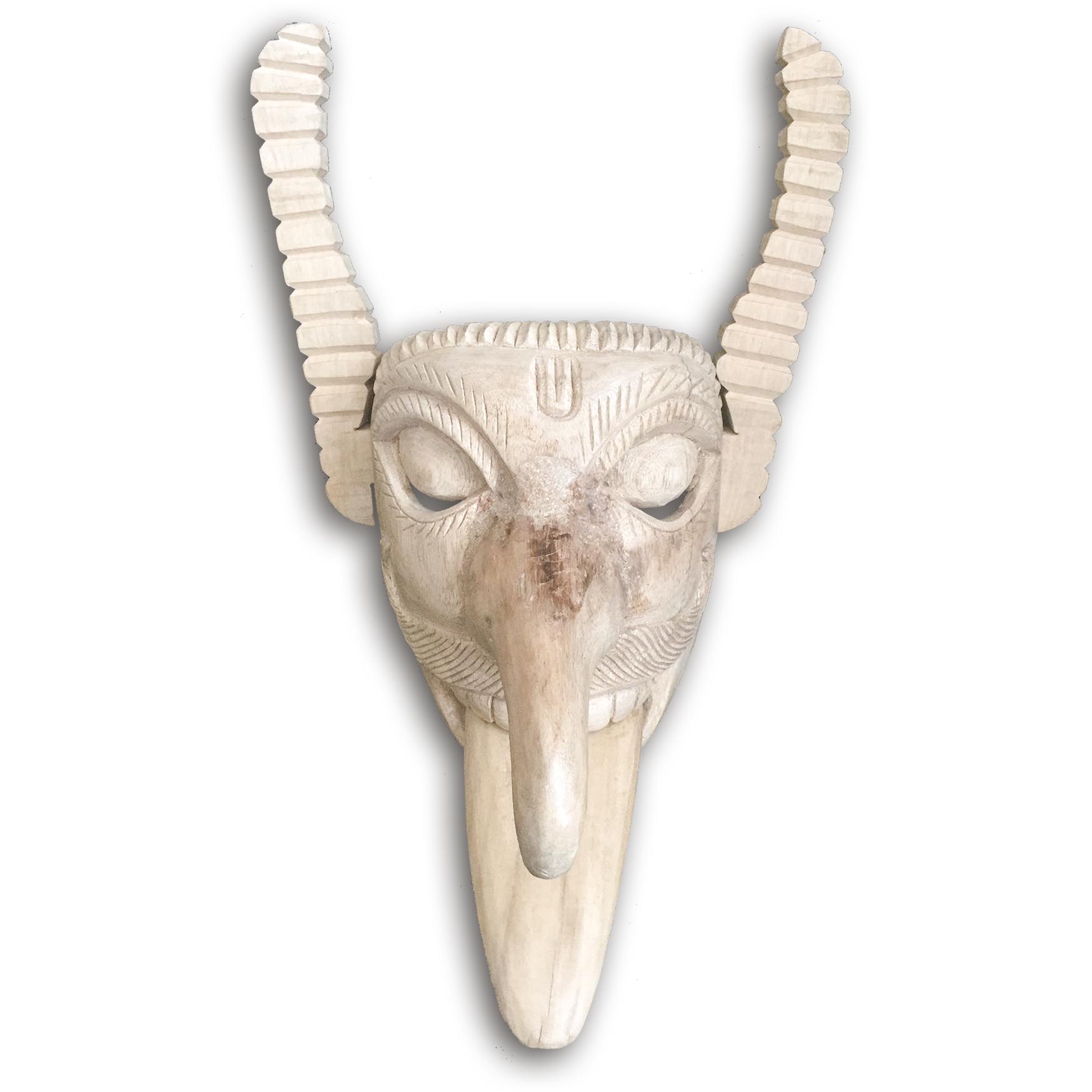

Mukhosh (mask) making is an ancient craft form that dates back centuries. Although a craft shared throughout Bengal, the masks are fiercely individual. Each region utilises different techniques to create their individual Mukhosh, and the materials used are just as diverse as the state of Bengal.

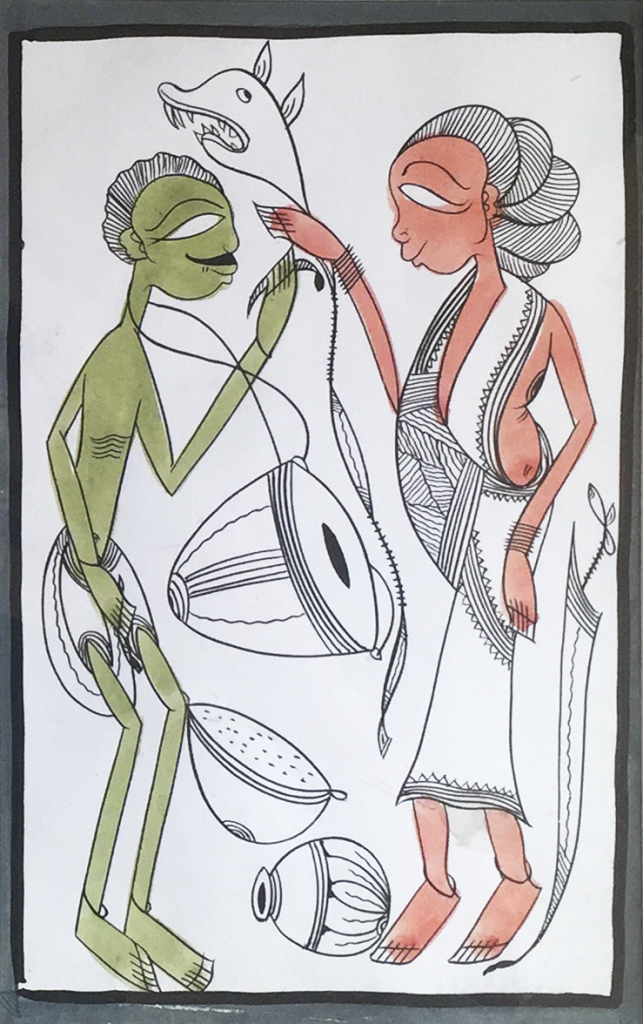

Patachitra, a visual storytelling style takes the form of painted scrolls, depicting sequential scenes from stories, legends and myths. What makes modern Patachitras so enchanting is their ability to portray important social themes and the demons of our day, like gender inequality, child marriage and climate change whilst staying true to the ancient and mesmerising style. Just as mask makers make use of nature in their work, Patachitra artists make their paints from natural colours from locally available flowers, leaves, fruits and other natural materials.

Biswa Bangla is passionate about a place for arts and crafts in today’s international art world. It is our hope that you will share it with us, paving the way for the future of Bengal’s arts and crafts, as well as its creators.

Masks

Although a craft shared throughout Bengal, the masks are fiercely individual. Each region utilises different techniques to create their individual Mukhosh, and the materials used are just as diverse as the state of Bengal, with wood, clay, paper and metal all part of the process of creation.

Perhaps the best place to start is their affiliation with powerful witches, who according to Bengali folklore, brought the masks into being as a way of concealing their identity. The rich colour and flamboyant designs were also intended to attract innocent victims, sacrificing them in return for immortality. The initial genesis of the mukhosh began with great religious importance but now masks find themselves an integral part of many different dance forms, used symbolically to appease the demon gods and usher in peace and prosperity. The masks were a replacement for text, for the many illiterate the masks conveyed myths and religious icons in a visual format. Traditional mask dance still exists in many districts of Bengal, and the enchanting power of the masks is still as present as it ever was.

Shankar Das is a leading mask maker from Sabdalpur, a village in the Dakshin Dinajpur district of West Bengal. The talent of Das’ artistry is illustrated by the presentation of a State Award for his work. Das plays a leading role in managing a collective of mask makers at Kushmandi and participates in fairs all over India.

Clay Masks of Ghurni

The Ghurni region of Krishnanagar in Nadia district has been a notable centre of clay art for a long time. Its popularity lies in the colourful, fired clay dolls. For the last few years, the artisans in this area have started experimenting, creating masks of a more contemporary style.

Kumartuli’s Clay Masks

Kolkata’s Kumartuli is well-known for its statues of deities and this mask here is an incarnation of the goddess Durga. Durga has countless forms, many of which are present through the exhibition. Initially made in clay and then sun-dried, the masks are then coloured and finally decorated with sponge wood or foil.

Shola (Sponge Wood) Masks of North Dinajpur

Sponge wood masks are used in the ancient Gamira dance of North Dinajpur. To create these striking masks, the artisan first prepares a model from mashed paper. After layers of cloth, mud water and sponge wood, powdered colours are mixed with water and painted onto the face. The glow is achieved through a varnish polish. Finally, it is decorated with sequins, foil, and coloured paper.

Banabibi Pala Masks

The Banabibi pala is a popular folk-theatre of the Sunderban region. The short play is centered on the conflict between Banabibi, the guardian spirit of the forests and Dakshin Rai, a demon king. In the end, Banbabi emerges victorious over the wicked Dakshin Rai. It is believed that Dakshin Rai actually appears in the disguise of a tiger and attacks local villagers.

Dokra Masks

These bronze masks are created through metal casting by the lost wax process, this unique folk art of West Bengal is known as Dokra. Gita Karmakar of Bankura has created various contemporary sculptures with this art form and has been presented the President’s award for her beautiful works. The versatility of this craft is endless and Dokra masks are used for décor and as symbols to ward off an evil eye. This demon mask and the goddess Durga are perfect illustrations of a timeless theme that has encaptured generations.

Shola Masks from Murshidabad

The intricate detail of these masks is carved from the root of the shola tree. The Murshidabad district in West Bengal is particularly renowned its shola creations. While these masks mirror the Dokra masks in theme, the goddess Durga, the wonderful diversity of Bengal can be seen through the variation in style, technique and the way the goddess is portrayed.

Kushmandi Masks

Kushmandi masks are associated with the Rajbangshi community, where 150 artists are working with wood to create very specific types of masks. The Gamira mask of Kushmandi is made from the wood of the Gamar tree. The wood is soft and easily chiselled, allowing the craftsmen to create intricate designs. Kushmandi is also home to a selection of gilded masks. Like the one you see here, they are crafted initially using wood and the base of the mask is then coated in thin sheets of Italian gold. The use of materials is as rich and diverse as the state of Bengal itself. The Kushmandi masks are donned by Gamira dances as they perform in festivals, retelling ancient myths and tales that are specific to their community and its story.

Chau Dance Masks of Purulia

‘Chau’, which means fun and frolic, is a dance of the hardworking population of Purulia. The Chau dance is performed during the festival of Chaitra Sankranti. Traditionally, tales relating to the deities were the theme of the dance. Chau dancers perform only on mythological themes. Chau is a dance of the brave hearts, a dance of war, where the mask is an inseparable part. These world famous masks are made by the artists from the Sutradhar community.

Masks of the Bagpa Dance

The Bagpa dance is a part of tantrik Buddhism and was conceptualized by Guru Padmashambh. It’s a war dance based on the theme of the destruction of evil and the well-being of humanity. Different characters are created through various wooden coloured masks. Kajimal Golay, a well-known artist of Bagpa dance masks and a researcher set up the Dooars Museum and Research Centre for the revival and spread of the dying arts of the communities living in the Himalayan region.

Rabankata Mask

This mask is an incarnation of the evil Ravan, a demon destroyed by the goddess Durga and is used in a dance during Durga Puja in Bishnapur of the Bankura district. Started between 1626 and 1656 B.C. the dance is focused on the victory of good over the evil.

Masks of the Gambhira Dance

The Gambhira dance is performed during the festival of Chaitra Sankranti all over the Malda district of North Bengal. It is a solo dance revolving around mythological characters. Made by the local Sutradhar community, the masks are created from neem and fig trees, and occasionally clay. First, the facial features are carved out from a piece of wood and later coloured according to their character.

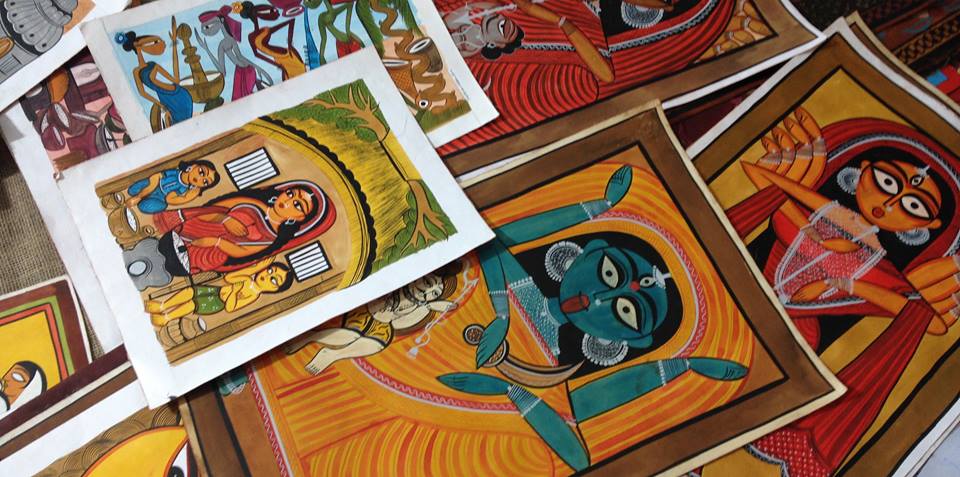

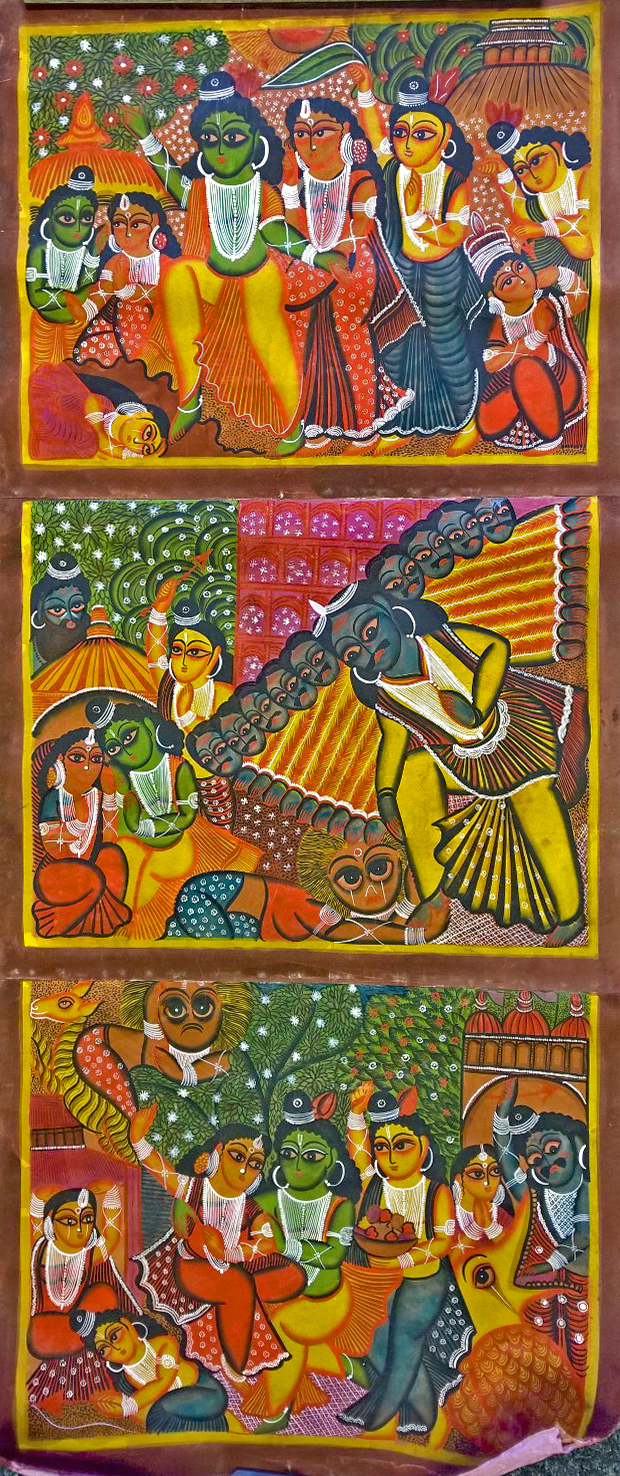

Patachitra

The subjects of Patachitras have seen a shift in the passage of time, just as our perceived concept of Gods and Demons has. Patachitra subjects began their journey with religion and folklore, nowadays the paintings depict contemporary events like terrorist attacks, tsunamis and earthquakes. The traditional themes of Patachitra passed through the generations of patuas for many years. Indian mythology, lives of the female deities and other religious figures have been incredibly popular subjects. Patuas also painted Hell onto their canvases, grisly depictions of Lord Yama, the God of Death, were used to warn off sinners. Art has been used in religion as a way of warning laymen throughout the world for thousands of years, the gruesome images on the Patachitras can easily be likened to gargoyles and stained glass windows in western churches.

The accompaniment of the songs during the unravelling of the scrolls draws together multiple creative worlds, a concept that contemporary artists are incorporating into their work. Patachitra acts as a form of both education as well as entertainment. The stories that that the patuas sing are mainly tales of morality, and in this sense, they act as social reformers as well as entertainers.

A young artisan from Naya, a village in West Bengal, Suman Chitrakar has mastered the traditional Patachitra artform, applying it to modern day products such as; painted bags, apparels and crockery. Patachitra’s influence on today’s artistic community can be seen in its similarity to graphic novels and comic books; a world that Chitrakar is also involved with.

Rolled Patachitra

India has a long and rich history of rolled Patachitra; patachitra stems from the word ‘pata’ meaning fabric or a silk cloth. These rolled patas can be horizontal or vertical and come in the size of 2 meters by 10 or 20 cms. The stories of the scrolls are brought to life by singing scroll painters, known as Patuas. Originally they travelled between villages, singing their stories whilst unravelling and painting the scrolls, illustrating the stories and bringing them to life in another visual dimension. Though rolled patachitra performances have lost their popularity in the villages, they are gaining popularity on an international level, the most sought-after style being the multi-coloured Manasa patachitra.

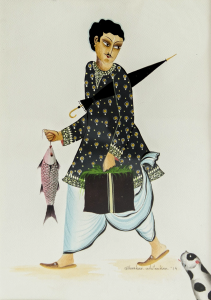

Kalam Patua

Kalam Patua is an artist from West Bengal, reviving the ancient art form. Having studied the traditional kalighat Patachitra, the characteristic bold lines and bright colour of Patachitra is clear in his work. Although the painting here depicts a traditional subject, many of his paintings are often scenes of the Indian middle class in contemporary settings, simply watching television or riding motorcycles.

Lakshmi Sara (Goddess Lakshmi on earthen plates)

The goddess of wealth, Lakshmi has always been worshipped in various ways. Throughout Bengal, especially Dhaka, Faridpur and Barishal, colourful Lakshmi saras (earthen plates) were made during the festival of Lakshmi Puja. This is done before applying a layer of chalk dust. After drying, black lines are drawn to divide the painting area and various designs are painted between them. When the colours are dry, the painter paints the goddess Lakshmi, an owl, rice, shells, etc. These are drawn quickly with a brush made of thick bristles. The simplicity of the drawing and lines and use of colours represent this tradition of Bengali folk paintings perfectly.

Dasavatar Playing Cards

Dasavatar means ‘incarnation’ and painted onto these cards are the 10 avatars of Lord Vishnu; Matsya, Kurma, Barah, Nrisingha, Baman, Ram, Balaram, Parshuram, Buddha and Kalki. Dasavatar cards are a part of the rich heritage of Bishnupur in Bankura, the ‘Dasavatar card game’ is complicated and is played using 120 cards. The Faujdar family of Bishnupur specialize in making these beautiful and unique examples of Bengal’s folk art.

Santhal Patachitra

Patachitra is a significant part of Santhal tribal communities in West Bengal and are very different from others in terms of subject and dramatization. They are commonly known as ‘Patakir’ or ‘Patakatar’ and come in three kinds:

- Ancient Patachitra: It explains how God created these patachitras with the help of the deities of the Santhal community, Marangbaru, Litagatte and Jaher Era

- Maharaja Patachitra: Whenever a human went missing in the forest, these patachitras would provide a likeness of the person and provide information on where he may possibly be

- Jadu Patachitra or Heavenly Patachitra: This grisly presentation of the punishment given by Marangbaru for earthly sins is made when a person dies. On the death of a Santhal member, the Jadav patuas would draw a human figure without eyes, but surrounded by various objects and utilities. They would bring the object to the family and ask for a fee to draw the eyes, explaining how traumatic it would be for the deceased to be sightless in heaven.

Kalighat Painting

These style of paintings depicted contemporary society usually under satirical scrutiny. Kalighat paintings flourished during the British raj in India and are a harmonic balance of the artistic ideas between oriental themes and occidental techniques. With the rise of the city of Kolkata as the centre of the British Raj, people from rural Bengal began to move to look for better livelihoods. Gradually, the area around Kalighat temple transformed into a bustling business centre. Among those who settled down at Kalighat were the Chitrakar and Patua artists from South 24 Parganas and Midnapore. The urbanization of Kolkata inspired them to introduce a different kind of painting, done with bold, strong strokes. This came to be known as Kalighat Patachitra. The intellectual discourse of the elite or the vulgarity of the babus was often subject to satirical observations in the Kalighat Patachitra of the time.

Manuscript of Mahishadal

Just a few of the ancient manuscripts discovered in West Bengal carry pictures. One is the rare, multi-coloured Ramayana of Mahishadal from East Midnapore. It was written in the 18th century for the personal reading of Queen Janaki of Mahishadal. The manuscript has colourful pictures in all the 343 pages representing various events of the epic Ramayana, such as the wedding of Ram and Sita, the war between Ram and Ravan, the killing of Marich and Taraka, and many more. Mostly two-dimensional, the magnificent use of colours and lines has made it a masterpiece of pata art. Compared to the Patachitra of Midnapore, it is interesting to see how the styles and techniques of Patachitra have developed over time.

Patachitra of Midnapore

The painting of Patachitra is a collaborative activity, in which members of the community help to paint the patuas story. The patua community has been living in the Midnapore district since ancient times. Patuas would share their rolled patas throughout local villages. Curious on-lookers would anxiously wait to see how the pata unfurled with the song, revealing pictures of Hindu deities, as well as local scandals and political events. Owing to fast urbanization, rolled patachitra is now a dying art; whilst square ‘Chuoko’ patachitras are gaining in popularity. These chuokos were originally used when a member of a tribal village dies; a likeness of the deceased, without their eyes, is painted onto the square canvases. The patuas would then show the patachitras to the mourning family, singing of how agonizing it would be if the dead one reached heaven without his eyes. The bereaved family would then pay the patuas to complete the picture by painting the eyes. Chuoko patas inspired art in Bengal throughout history, an urban incarnation can be seen in Kalighat paintings.

There is a strong individual identity in Bengal which is demonstrated by the diverse arts and crafts throughout the state. Biswa Bangla love this strong individualism and are passionate about the diversity which characterises the state. ‘Where the world meets Bengal’ symbolises exactly what we want to achieve through our exhibitions and showcases. It is our hope to share the stories of the masks and paintings with the rest of the world, creating a future for the both the arts and crafts of Bengal, as well as the craftsmen.

by Jasmine Pepler

London

Nehru Centre

3rd to 6th May 2016